More data, analysis and dialogue are needed to avoid costly mistakes

Governments have traditionally used targeted interventions known as industrial policy to make domestic producers more competitive or promote growth in selected industries. While some developing countries continued to use it, industrial policy fell out of favor across most of the world for years, because of its complexity and uncertain benefits.

Now, industrial policy appears to be back everywhere. The pandemic, heightened geopolitical tensions, and the climate crisis raised concerns about the resilience of supply chains, economic and national security, and more generally about the ability of markets to allocate resources efficiently and address these concerns. As a result, governments came under pressure to have a more active industrial policy stance.

Economists have long debated the merits and drawbacks of industrial policy. These measures can help address market failures, such as interventions related to the climate transition. But industrial policy is costly, and can lead to various forms of government failures ranging from corruption to mis-allocation of resources. Industrial policies can also lead to damaging cross-border spillovers, raising the risk of retaliation by other countries, which can ultimately weaken the multilateral trading system and worsen geoeconomic fragmentation. More data, more analysis and more dialogue are needed to avoid costly mistakes.

In this blog, we unpack the return of industrial policy and ask three questions about what is driving this resurgence, the trade-offs that it raises, and what the IMF is doing about it.

The new wave

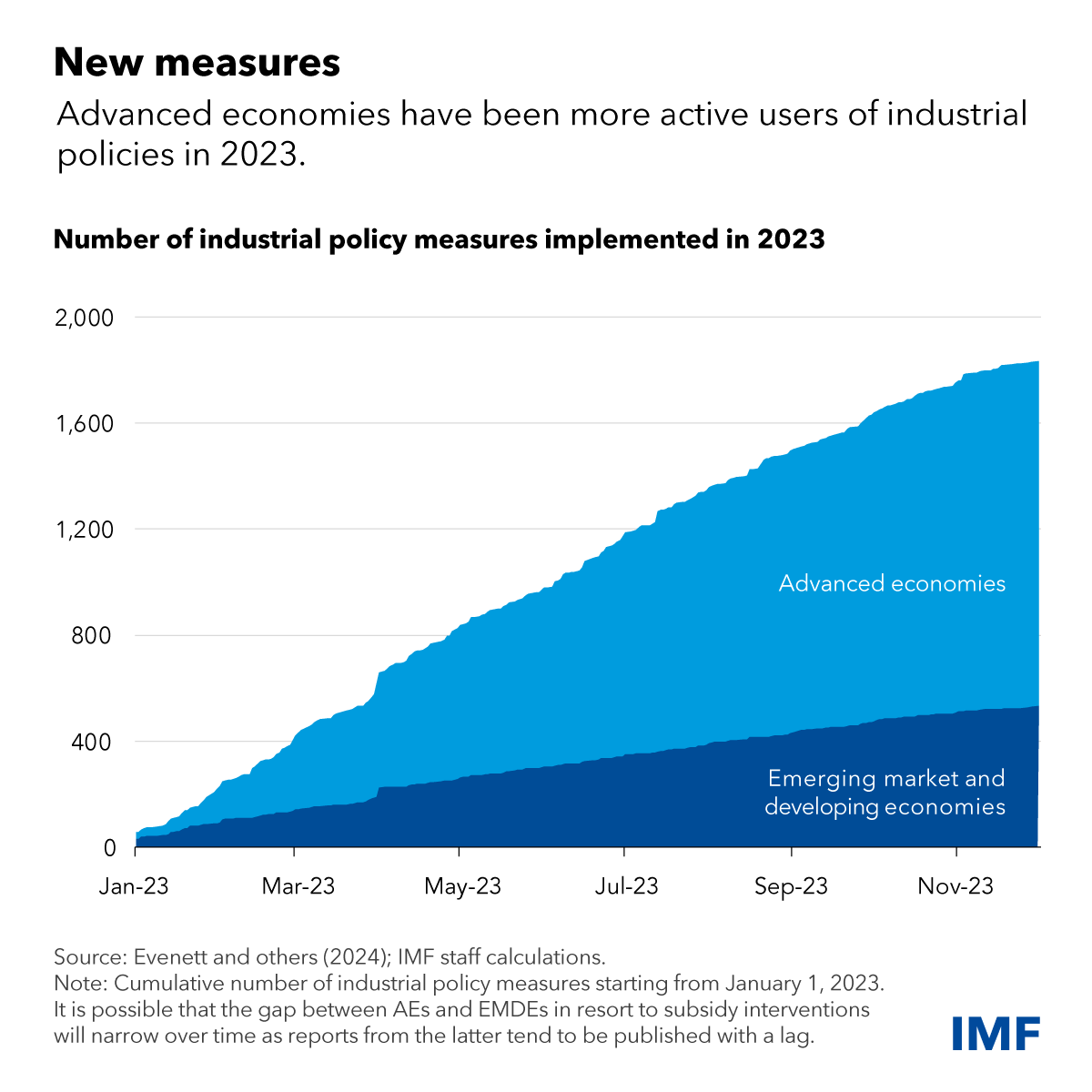

The IMF recently joined forces with the Global Trade Alert to monitor developments. Our new research shows that there were more than 2,500 industrial policy interventions worldwide last year. Of these, more than two thirds were trade-distorting as they likely discriminated against foreign commercial interests. This data collection effort is the first step toward understanding the new wave of industrial policies.

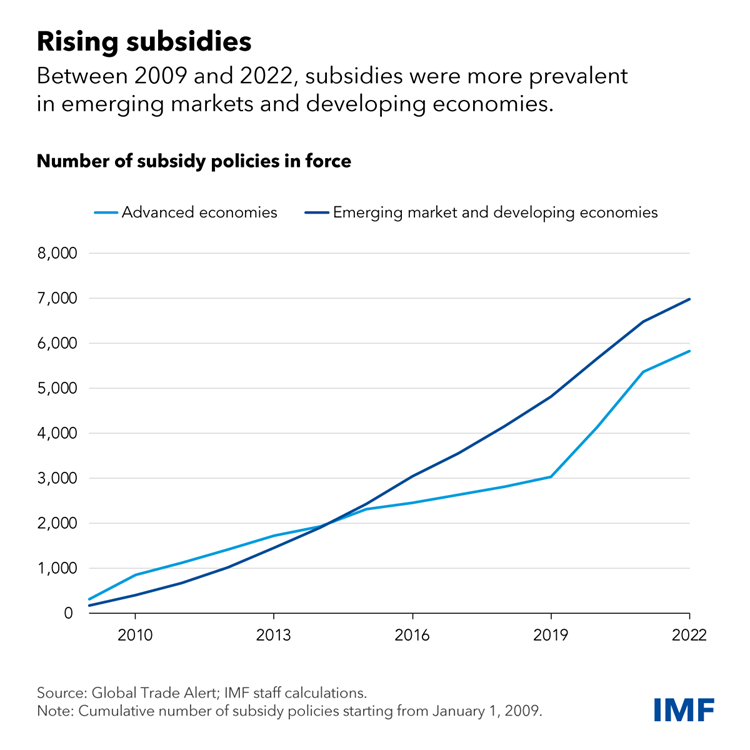

The recent surge in such measures has been driven by large economies, with China, the European Union, and the United States accounting for almost half of all new measures in 2023. Advanced economies appear to have been more active than emerging markets and developing economies. Data for the past decade are less precise, but the available information shows that the use of subsidies has historically been more prevalent in emerging economies, contributing to large number of legacy measures still in place.

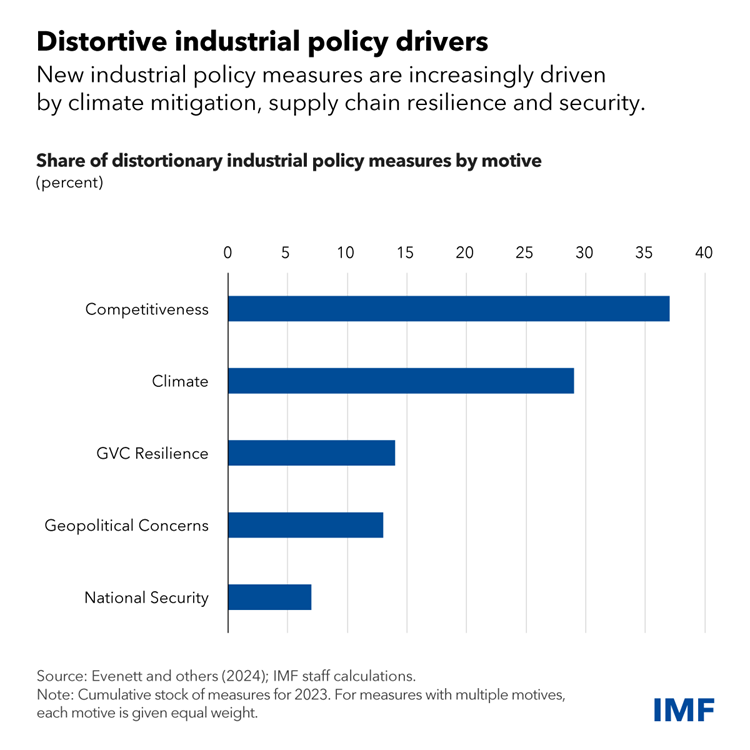

Recent measures focus more on the green transition and economic security, and less on competitiveness. Competitiveness was the objective for one-third of all industrial policy measures last year. The remaining two-thirds were motivated by climate mitigation, supply chain resilience, and security considerations.

Interestingly, the most-active sectors were military-civilian dual use products and advanced technologies, including semiconductors and low-carbon technologies, as well as their components, such as critical minerals.

Industrial policy steers a reallocation of resources toward certain domestic firms, industries or activities that market forces fail to promote in a socially efficient way. To deliver net economic benefits, however, these interventions need to be well-designed, which means they need to be directed to address well-identified market failures, and based on competition-enhancing principles and sound cost-benefit analysis.

Since industrial policy aims to alter incentives for private companies, it also entails a risk of resources being misallocated and governments being captured by industries over time. It can also affect trade, investment, and financial flows as well as global market prices which could have significant implications for trade partners and the global economy.

IMF staff’s recent analysis of the new industrial policies underscores the need for caution.

- Measures announced or implemented last year were not always clearly related to market failures. This means that in some cases well-designed policies aimed at improving the general business environment would have been more appropriate than targeted government interventions which carry a risk of misallocating resources and potentially significant fiscal cost.

- Staff’s research provides further evidence of a tit-for-tat dynamic. The odds of interventions focusing on a certain product are higher if it was the target of interventions by other trading partners. In fact, measures such as subsidies often create cross-border spillovers that may induce other governments to react in a similar way.

- There is also some evidence that industrial policy can be captured by special interests. Analysis shows a high correlation between the number of measures and political economy variables such as the presence of an upcoming election and the importance of certain products in the export basket, which indicates that governments may favor established companies.

The IMF’s role

Given the novelty and macro-criticality of many recent industrial policy measures, IMF staff has stepped up work in three areas.

The IMF has increased focus on collecting data and providing analysis of industrial policies to increase awareness and inform policy discussions. In addition to the new data monitoring initiative, staff examines the effectiveness of industrial policies in achieving stated objectives, such as innovation (see the April 2024 IMF Fiscal Monitor) and climate goals, as well as their cross-border spillover effects.

- In bilateral surveillance, IMF staff focuses on assessing industrial policy measures that can significantly affect the country’s domestic or external stability or have the potential to generate significant cross-border spillovers. The scope of staff’s analysis and policy advice depends on the type of industrial policy and its objectives, as well as on available information and expertise. Two recent IMF papers provide a conceptual framework and guiding principles for the coverage of industrial policy in IMF surveillance, including trade-related issues and consistency with World Trade Organization rules.

- Finally, the IMF is collaborating with the WTO to promote a multilateral dialogue on trade and industrial policy. A technical meeting on policies for resilience already took place in February with contributions from several countries and other international organizations. The goal is to deepen and broaden this work in the coming months. Discussions like these can improve information-sharing on enacted measures, their effectiveness and spillovers, and help develop a common understanding of the issues and possible cooperative solutions.